Have you ever listened to music that lifts your spirit after a difficult day? Your heartbeat slows down to an even, relaxed thump, and all of your anxieties dissipate. In almost every culture, this kind of music exists. It’s ancient. It’s free-flowing. It’s sacred. Amongst ancient peoples such as the Mbuti of the Congo, there are songs for hunting and the successful collection of honey. While Uighurs in the Xinjian region of China have muqam, ‘the mother of all Uighur music’ which explores everything from the celebration of love to musings about everyday life. And there’s more: The traditional Midsummer folk song from the Aukštaitija region of Lithuania, which is sung during the summer solstice celebrations, the arrows ritual song from the Xikrin people of the Amazon rainforest, the Oriori (lullabies) of the Māori peoples in New Zealand, and more. And it’s Seattle Sacred Music and Art (SAMA) mission to bring this sacred music from around the globe to Seattle stages and screens. Since it was founded by John Goodfellow and Darek Mazzone in late 2019, SAMA has featured dozens of in-person and live-streamed performances from international sacred music artists every week. I had an opportunity to speak with KEXP DJ and SAMA curator, Darek Mazzone, about his vision for the organization and the power of sacred music.

“It's a village, and the village could be anywhere,” Mazzone said. “And people are getting together for a meal, and it might be a funeral or a wedding or a baptism or something. And there are musicians there that are just playing unmetered music. So, they're playing violin. They're playing horns. But it's not metered. It's not set to dance or anything like that. And having that music actually prepares your heart. It prepares your emotions for what is coming a little bit later with this music, which is to get people to move, to get people closer together, to get people to share a common experience. And that is the difference between a lot of stuff that we're seeing right now in pop music versus a lot of these ancient traditions.”

Pop music, in many ways, is the pulse of the present moment, often reflecting the joys, heartbreaks, and aspirations of a generation. It's timely, catchy, and designed for mass consumption. It resonates with the here and now, giving voice to the contemporary collective consciousness. However, its ephemeral nature can restrict its depth, making its themes fleeting and solely relevant to current trends and sentiments. Once the moment passes, some pop music falls into irrelevance.

Songs like Video Killed the Radio Star by The Buggles (1979) and Operator by Midnight Star (1984) may no longer completely resonate with today’s audiences because of outdated references such as the prominence of radio stars, payphones, and telephone operators.

In contrast, sacred music delves into the timeless and eternal. Rooted deeply in tradition, culture, and spirituality, it transcends the immediate and addresses the immutable aspects of the human condition. While pop music may recount a summer love or the thrill of a night out, sacred music grapples with overarching themes of life and death, hope and despair, divinity and humanity. It is steeped in ritual, history, and a collective memory that binds communities through centuries.

Sacred music helps communities “deal with difficult times,” Mazzone said. “Whether it's like, ‘Hey, a war is coming. We don't know if we have enough food. There might be a famine.’ Or, just like the day-to-day life in ancient times and what could happen or not happen. These were the musical expressions of that. Right now, and this is overly simplistic, a lot of the music is just to celebrate happiness, celebrate one moment… I'm trying to get people to open up their hearts to other places,” Mazzone said. He describes himself as a cultural activist who uses music to change minds. “I'm seeing a lot of closed hearts right now. Closed hearts all over this country and other parts of the world, and a lot of fear. And I find that with music as an artform, it allows people to let go of fear and it opens up their hearts.”

Mazzone said that his curatorial vision for SAMA is in the spirit of his KEXP series “Musical People Being Bombed.” In that series he plays music from artists living in war zones, especially countries being bombed by the U.S. military. He wants people to look past the destructive propaganda and the ‘us versus them’ mentality that war brings, and see the humanity of people who may be different but only superficially.

“I find that when I present music from different cultures, it's not like a direct attack like sometimes you find with social activism,” said Mazzone, who also explained why he considers himself a cultural activist and not a social activist. “With social activism, it's a direct attack. ‘You're wrong. You're stupid.’ I find that [cultural activism] is like a flank. It gets people to think about this outside of their shields.”

While growing up in communist Poland in the 1970s and 80s, Mazzone was exposed to musical expressions tied to nature, the seasons, and community; deeply rooted in Poland’s strong agrarian traditions. However, music was under the tight restrictions of the communist state which controlled the means of production and distribution, and often censored lyrics, themes, and styles considered ideologically dangerous. But within the quiet confines of his grandmother’s village library, Mazzone freely explored sacred music from around the world. Fortunately, Poland was far from being totally isolationist. The country welcomed many international students from places such as Angola, Mozambique, and Vietnam. And these students brought their musical traditions with them.

Such cross-cultural exchanges were embodied by events like the Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Music (Warsaw Autumn) which was founded in 1956 during a time when state controls on cultural expression had eased. The festival acted as a bridge between music artists in the East and the rest of the world. However, behind the scenes, festival organizers walked a tightrope, balancing artistic freedom and adherence to government mandates while under the ever-present watchful eyes of communist-era censors.

Sidebar: The Sounds of Defiance – Polish Rock in 1980s

The 1980s — amidst martial law and the solidarity movement in Poland— witnessed the emergence of rock bands like Kult and Maanam. Using coded language, their songs echoed the socio-political unrest of the time.

While Poland’s music landscape had been shaped by 1,000 years of history, with periods of war, invasion, occupation and eventual sovereignty, halfway across the world, the United States’ own unique musical traditions were emerging.

Some of the most enduring and globally recognized sacred music from the U.S. are Negro Spirituals like Wade In The Water, which explores themes of liberation and deliverance and was used by Harriett Tubman to warn people escaping slavery to step into a body of water to avoid the slave catchers’ tracking dogs.

Here’s a modernized version of Wade In The Water, performed by a London based choir:

There’s also Native American Flute Music which is an amalgamation of indigenous flute music from various tribes (e.g. Lakota, Kiowa, Pueblo, Creek, and Navajo peoples). Traditionally, flute music was used in storytelling, meditation, healing and courtship rituals, and various ceremonies. But today this music is often integrated into new age, ambient, and rock music genres.

Carlos Nakai’s Earth Spirit is a popular Native American Flute Music album. Take a listen:

And finally, Appalachian Sacred Harp music, which originated in New England in the 18th and 19th century, would eventually become most popular in the American south. This music tradition uses a "shape note" songbook, a system designed to teach people to sing even if they can’t read music.

Listen to the song Idumea also known as And Am I Born To Die:

Even as the American and global sacred music evolves, new sacred music is being born. In my research for this article, I found that hundreds of people had taken Chief Seattle’s profound speeches and set them to music, creating nascent sacred songs that reflect the indigenous struggle post-colonialization.

This type of musicalization of Chief Seattle’s Web of Life speech is in the tradition of Powwow Honor Songs with their signature steady drumbeats and vocal chants celebrating the great deeds and qualities of the person being honored.

Seattle's Rich Tapestry of Sacred Music

Seattle Sacred Music and Art (SAMA) offers locals a refreshing glimpse into the ever-evolving world of sacred music. It’s mission to showcase artists from around the world on Seattle area stages and screens promise to give Americans access to music they’ve probably never heard before, all without needing to leave home.

“We don't get a lot of artists coming through Seattle or the Northwest in general from different parts of the world,” Mazzone said. “They usually just go to New York and they think they've been to America. … We need to make sure that our cultural institutions, the venues, and all the things that make Seattle unique in its ability to foster and grow art and music from all over the place, stays as strong as possible.”

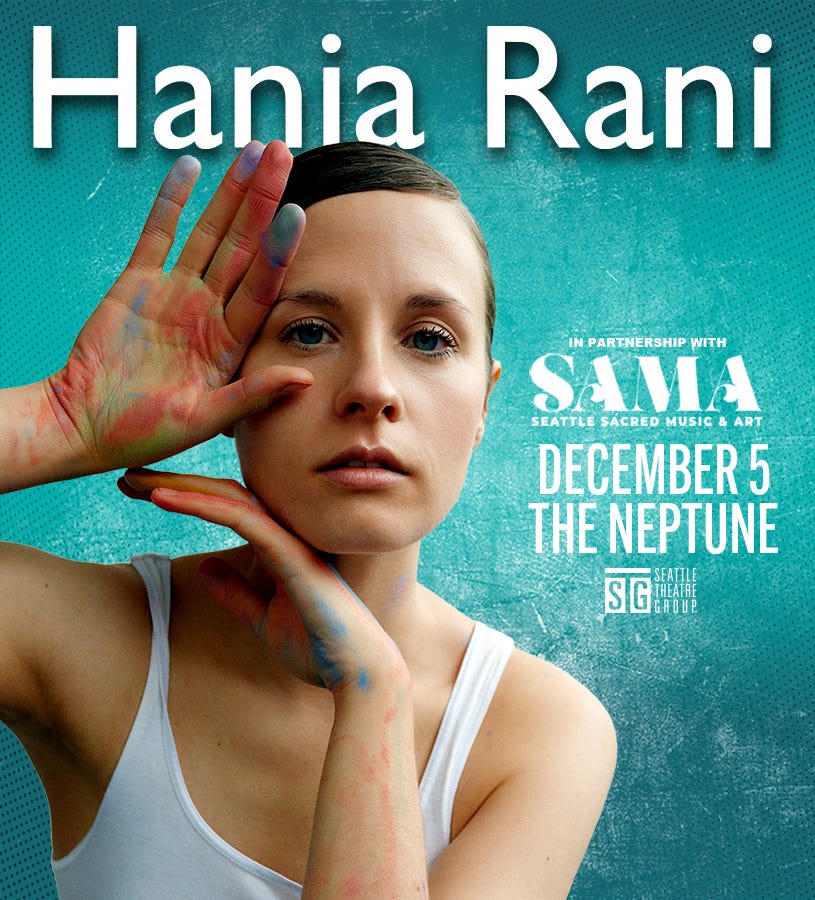

SAMA has already exposed the Seattle music scene to international acts like AL BILALI SOUDAN of Timbuktu, Mali; Groove& of Seoul, Korea; and Gaspar Varela of Lisbon, Portugal. But this is just the beginning. SAMA has a full calendar of upcoming events featuring sacred music from multiple continents.