Reclaiming Indigeneity

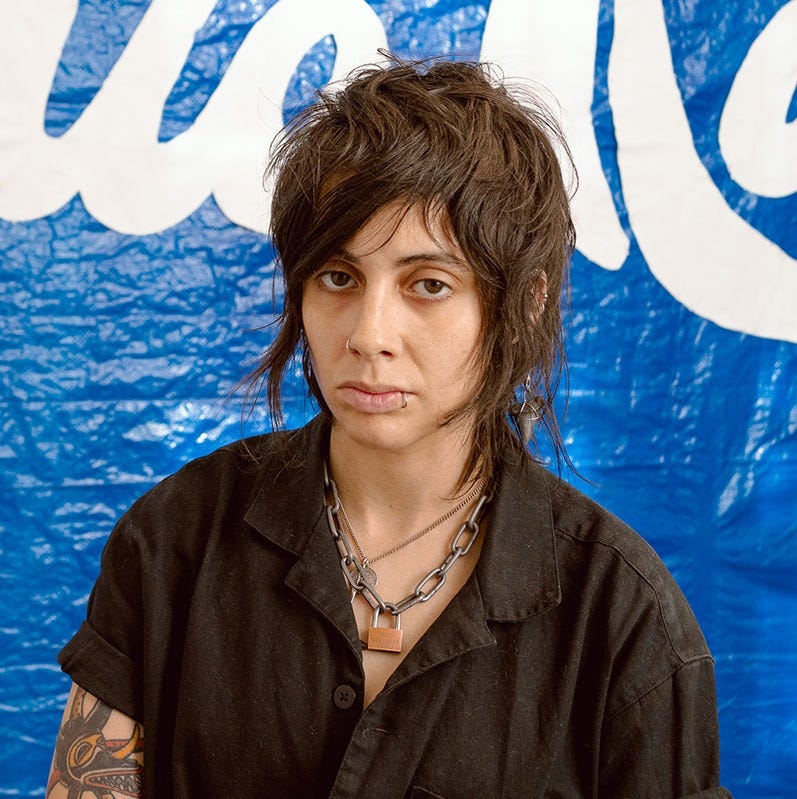

Boricua multimedia artist Jo Cosme uses virtual reality and lenticular photography to confront the settler gaze and reclaim land, memory, and Indigenous identity.

From the bioluminescent floors of Mosquito Bay to the volcanic black sands of Playa Negra, Puerto Rico’s uniquely beautiful and diverse beaches tell a story of geological wonder and ecological richness. Yet access to Borikén’s shores is shaped by a complex history of colonialism, conservation, cultural resilience, and community resistance.

Boricua multimedia artist Jo Cosme subtly explores these dynamics in her virtual reality component in her exhibition Welcome to Paradise: ¡Viva Puerto Rico Libre!, which transports viewers to a pristine beach rarely visited by outsiders and fiercely protected by locals.

“I wanted to make the colonizer salivate,” Cosme said of her choice of location. Puerto Rico has long been portrayed in Western colonial propaganda as a place to conquer, she explained—so she chose to feature a space that has not been conquered, even as it exists within what is often called the oldest colony in the world. “The beach that I recorded is a beach that is still very precious to us native Boricuas,” she said. “And I have not seen one U.S. person there yet. And I feel like it's been kept a secret.”

Since the United States seized Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American War in 1898, Boricuas have lived in a kind of political purgatory. As an “unincorporated territory”—a euphemism for colony—Puerto Rico exists at the mercy of U.S. federal power. Its people are U.S. citizens, yet they cannot vote in presidential elections and have no voting representation in Congress. For more than 400 years under Spanish rule and over 125 years as a U.S. colony, the people of Borikén have fought for autonomy, sovereignty, land rights, and both financial and cultural survival. Today, that struggle continues under the growing pressures of displacement, privatization, austerity, climate catastrophe, and disaster capitalism.

Jo Cosme’s creative work serves as a powerful lens through which U.S. audiences can witness the harsh realities Boricuas endure—it is also a clarion call to fiercely advocate for Puerto Rico’s liberation.

In Gringo Go Home, which is part of the Welcome to Paradise exhibition, Jo Cosme’s use of lenticular printing—a technique that causes images to shift depending on the viewer’s angle—is more than a visual trick; it’s a deliberate strategy to expose the skewing of perception under colonial and touristic gazes. By layering contrasting images—such as an untouched beach transforming into a neglected, trashed shoreline—Cosme forces the viewer to reckon with the dual realities of Puerto Rico: the fantasy sold to outsiders and the truth lived by Boricuas. This shifting visual field mirrors the dissonance between how tourists consume Puerto Rico as a paradise and how locals experience it as a contested, endangered homeland. The lenticular format refuses static interpretation; it demands movement, attention, and a confrontation with colonial narratives, revealing what lies beneath. In doing so, Cosme not only exposes the superficiality of the tourist gaze but also reclaims visual power, allowing the land itself to tell a more honest story.

“Something that I would like people to really think about is that when they travel, sometimes they're not aware of what's happening on these places, politically speaking,” Cosme said. “And so, they behave in a way that makes us feel uncomfortable. They forget that people still live here and that we are being pushed out by people like them.” Cosme explained that she has gotten into verbal disputes with new settlers and tourists especially when they respond poorly to being told ‘gringo go home.’ “If you read the news, you would just move, because there is a tension here, and you're coming here thinking it's going to be your little Caribbean paradise, your little vacation, but there are things happening in the soil right now that you have to be aware of when you travel…I want people to really try to look within and recognize how they can be a more conscious traveler, how they can invest more in the local people, or just not go to X or Y place in general. Just don't.”

Cosme lives the consequences of colonialism every day. Born and raised in Puerto Rico, she was forced to leave the archipelago after Hurricane María devastated the island in 2017—and the abysmal failure of the U.S. government to provide meaningful relief only deepened local suffering. Like many Boricuas, Cosme prefers life in Borikén, but staying often means battling just to meet basic needs, even as a new wave of settlers snaps up "cheap" land to build their version of paradise. Disaster capitalism—a term coined by writer and activist Naomi Klein—describes how investors exploit the aftermath of natural or manmade disasters to seize land, displace communities, and profit from redevelopment. Its victims are left with impossible choices: fight costly legal battles to hold onto their homes or focus on sheer survival. In Cosme’s case, the cost of staying became too high—not because she lacked roots, but because the system works against those trying to remain rooted in their homeland.

“It was a very conflicting to come into a country that oppresses your own country,” said Cosme. “But I do have a backhandedly imposed U.S. citizenship, which is—if you look at it in one way—a privilege to have. But that made me want to be like, ‘Well, if I'm in the States, how do I make myself useful while I'm in the oppressor country and I’m dealing with survivor’s guilt every day?’ I felt the urge—once I had the opportunity to have time and money—to start creating art again, because I feel this responsibility, and also like it's the only way I can deal with the shame of not being there and struggling with them.”

There’s a brutal irony in Jo Cosme’s forced migration: By leaving Borikén and moving to Seattle, Cosme gained access to resources—economic, intellectual, historical—that had been systematically withheld from her on the island.

“If you don't grow up with an academic background or class privilege, there's also not a lot of access to our own history in Borikén because we are constantly censored by our own government,” Cosme said. “We're not taught about a lot of uprisings, starting from the Taino. We're not taught any of this. We have to seek this information in order to learn. And I feel like it's also part of keeping us uneducated so we don't wake up.”

The lenticular image featured above powerfully illustrates the visual erasure of the local in favor of the imported. With just a shift in perspective, a sleek, contemporary house begins to dominate the frame—gradually obscuring, then completely obliterating the weathered, densely built structures inhabited by locals. The transformation suggests not only the physical displacement of Boricuas but also the erasure of their cultural memory in favor of settler fantasies and foreign investment. It’s a visual confrontation: Who belongs here? Whose story is being overwritten? Will the layered history and vibrant culture of Borikén be replaced by the sterile, ahistorical fantasy of the West?

The battle begins in the minds of Boricuas who have been subjected to multi-generational identity erasure. Through censored education, the erasure of Indigenous histories, and the imposition of U.S. cultural values, Puerto Ricans have been systematically disconnected from their own past and indigeneity.

“Some of us grow up celebrating our native heritage,” said Cosme, “which is Taino from the Arawak. But then we're constantly told that Boricua is a modern identity, and so we are reclaiming this indigeneity to the Caribbean, which has been taken away from us because of this imposed assimilation due to US imperialism, and before that, the Spanish. So, we were constantly taught that we cannot claim this indigeneity because they had killed off all of the Taino from the archipelago.” But because of genetic testing, Cosme went on to explain, it has been revealed that many Boricuas carry a high blood quantum of native ancestry, even as using blood quantum measurements is extremely controversial in some parts of the community. “That was kind of mind blowing to us, because we were always taught that isn't real. So, a lot of us have been trying to reclaim that identity. And for some of us—for instance, me—we have been born and raised within the community and the culture, and we practice it, we honor it, we take care of it. So, in the face of this assimilation and imperialism, the fact that they were not able to actually erase us from the map, is an incredible form of resistance.”

Later this month we will share the event audio of our conversation with Jo Cosme at Grocery Studios.

© Copyright 2025 - Artists Up Close/Beverly Aarons. All rights reserved.