The Artist's Body Remembers: Art Etched In Ancestral Memory

Can art carry ancestral memory? Visual artist Gary Logan explores this possibility through biomorphic forms, mysterious natural worlds, and a deeply personal creative journey.

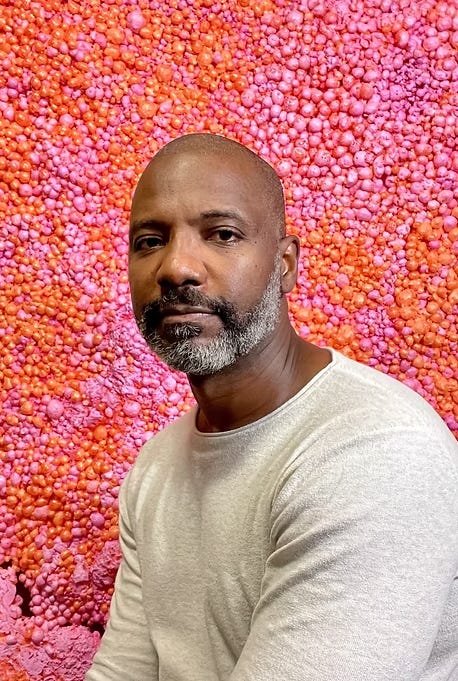

Every painting is a constellation of life—molecular and planetary—each shape, carefully crafted by Seattle-based artist Gary Logan, presses against and evolves the other. Born in Trinidad and Tobago but raised in the U.S. since he was five, Logan understands how the world can alter a person—their form, their trajectory, the way others perceive them. It’s this awareness that breathes life into every one of his artworks.

“Nature is definitely my muse,” said Logan who collects microscopic imagery from documentaries and scientific articles. “When I'm out on hikes, I'm usually with my cell phone or with a camera taking photos that I then bring back into my studio. The result ends up being these really bizarre like biomorphic forms and masses that are populating my canvases.”

Through these ethereal and primordial forms—sculpted from foam, acrylic, natural materials, and ancient memory—Logan traverses the complex terrain of the human condition: identity, race, and sexuality.

“I also do a lot of experimenting with a wide range of different materials,” Logan said of his ability to create heavily textured surfaces, “from natural materials like paper pulp to more synthetic materials, like polyurethane foam. And I work with both of those, as well as with paint, to really push the idea of blurring the lines between two-dimensional painting and three-dimensional sculpture—basically, like relief sculptures.”

From geological to biological landscapes, Logan’s abstract paintings carry heavy but taboo unspoken narratives. His artwork Raw Cotton In Brown Skin (2020) is a rectangular patch of deep brown cowhide with white cotton bulbs embedded in it. Beige strings emerge and dangle from the piece. This work evokes painful histories—stories of enslavement, extraction, and capitalism. The leather, tanned and shiny, represents how the enslavement of African bodies was profitable, acceptable, and even considered natural and inevitable in much of the US and Caribbean. And it isn’t lost on me that the cow—much like the enslaved African—has long been stripped of its sovereign and wild state, marked, from birth to death, to serve the lifeforce of others. Raw Cotton In Brown Skin captures this reality perfectly and instantly.

I remember once as a young kid going to a tar pit which we call Pitch Lake,” Logan said of his early connection to nature in Trinidad. “I remember that had a really profound impact on me. In fact, it actually still bubbles up in a lot of my artwork today. That lake that was this gorgeous, vastness of blackness, and some parts of it were kind of a dull grayish color and other parts were jet black while other parts were iridescent. And I remember my four- or five-year-old self just being transfixed by that. Here was this lake, something that's supposed to be filled with water that was actually filled with what we call pitch or tar.”

In Trinidad, Logan was free to be the boy who was curious about nature, unconfined by any negative narratives of the world around him. He was supported by not just his family but his community. Eventually, he would immigrate to the U.S. and everything would change.

“I didn't have access to nature in the way that I freely did in Trinidad,” said Logan of the U.S. neighborhoods he grew up in. In Trinidad, he knew his neighbors and could roam freely from one house to the next. No one thought much of a young boy exploring a local beach, but in the U.S., things were different. “My parents were very, very cautious and concerned about me not drifting too far from home, not talking to strangers. And I know for them there was also this concern because of the neighborhood that we were in. It was a predominantly white neighborhood, and you never quite knew who was going to be welcoming of you. So, there was always a sense of caution that I didn't really experience so much in my formative years in Trinidad.”

As Logan grew up, he began to deeply understand what it meant to be different and judged for it. He was often the only kid of African descent in his class. His peers mocked his accent. He worked hard to eradicate it. He wanted to fit in, to sound like everyone else. He was shrinking himself, that was the cost of acceptance. But then life changed again. He moved to North Florida in his early teens where he found his tribe and a more progressive and diverse space. He could grow there. He met people like himself. He reconnected to his Caribbean heritage and his emerging sexuality. He was gifted a microscope which opened the door to the unseen natural world. And he would eventually go on to deepen his love of nature and widen his awareness of other Black gay male artists like Mark Bradford.

“I was just blown away by his work,” Logan said of visual artist Mark Bradford. “To see work by another Black gay man was incredibly powerful for me. It also made me feel really hopeful that there was going to be a space for me and what I had to say in my artistic vision. The other thing about Mark Bradford's work that I think really opened a lot of doors for me was his use of a lot of nontraditional materials. The way that he uses paper, for example, is very different from what I had learned about in art school. And the way that he combines mixed media to create these incredibly textured surfaces, and also the abstraction that is very much intrinsic to his work, was really powerful for me because I think, in a lot of ways, I got this sense that what the art world really wants to see from a lot of artists of African descent is basically this limited idea of portraiture. There's a sense that in order for a work to be considered Black art, you have to see the Black body. And there was something about Mark Bradford's work that just really went below the skin for me, but at the same time was able to talk specifically and uniquely about his experience as a man of African descent. And I think it was around that time that I really gave myself even more permission to sort of free myself from what felt like the confines of figurative art in order to make comments about the Black experience.”

A graduate of the prestigious Boston University, School for the Arts, Gary Logan has a deep grasp of form, material, and conceptual nuance, but it’s the pull of ancestral memory that gives his work its unmistakable emotional gravity and conceptual depth. He draws from a collective recollection that lives not just in the mind, but in the body—etched into flesh, coded into molecules, and passed down through time.

“Is it possible that the struggles of some of my great-grandmothers had an impact on my development, on a genetic level, on my own psyche, and so forth,” Gary Logan asked of the impact of epigenetics. “It has been a theme that I've been exploring pretty consistently in my work that fits very much along with like what I want to talk about: The influence of nature in my work and how genetics might be playing a role in our lives. I mean, I definitely do believe in that balance between nature and nurture, but I'm particularly fascinated by how these two concepts really merged, especially when you think about epigenetics and the way in which maybe there are specific diseases that might be plaguing a population. And I do understand that a lot of it has a great deal to do with our ability to adapt; but I'm really fascinated by what might be lingering within our genes, especially the experiences that were really traumatic. And yes, there's a psychological way in which trauma can be passed on from generation to generation, but I'm really fascinated by the concept of how trauma can be passed on psychologically, but also perhaps even genetically.”

We know that all humans carry an epigenetic legacy that we usually associate with collective trauma and survival; but does that epigenetic inheritance also manifest in the art we create? Some artists and scientists say yes. Research into transgenerational epigenetic inheritance has shown that traumatic experiences—such as famine, war, and displacement—can leave molecular markers on DNA that influence how genes are expressed in future generations. In 2014, a landmark study from Emory University demonstrated that mice could inherit fear responses to specific smells—a finding that sparked broader discussions about how human responses to ancestral trauma might also be biologically encoded. Artists working within diasporic, Indigenous, and post-colonial frameworks have taken up these insights, suggesting that art itself can emerge from inherited memory—shaped not only by personal experience, but by the silent, cellular imprints of what came before. And while Gary Logan has explored these ideas in his work and his research, he doesn’t believe that epigenetic imprints should completely define who we are or what we explore in our art.

“I definitely want to create work that speaks to my experiences of what I'm witnessing in this day and age where there is still a lot of like racial strife and a lot of racial conflict,” Logan said. “But then there are times that I also just want to be a human being, and not just a Black man or not just a gay man that's creating art that's Black art or just gay art.”

As an arts journalist, I’ve interviewed many creatives through the years, and I’ve noticed that there is sometimes an additional burden placed on racialized artists to make visible (in their art) the pain they experience at being othered. And some racialized artists feel compelled to construct “looking glasses” so that others can catch a glimpse of their experiences. This can place them in the unenviable position of becoming essentialized, grotesque spectacles—visible but never truly seen. Again and again, artists tell me they want the freedom to explore the full depth and breadth of their humanity—not just their wounds.

“I'm also wanting my work to be speaking about universal themes, for example, our connection to and our impact on nature, and how we are radically transforming this planet to the point that scientists now have a name for this particular period: the Anthropocene,” said Logan, “a time marked by how human beings are radically transforming this planet like a force of nature. We have become a force of nature and there are times that I want my work to comment on those different ideas. So, being able to have the flexibility and the fluidity to speak about issues of identity as well as issues about my environmental concerns or our connection to this planet is something that I find myself having to give myself permission to do that.”

© Copyright 2025 - Artists Up Close/Beverly Aarons. All rights reserved.