A halo of snowy mountain peaks, leafy treetops, and temperate waterways encapsulates the iconic Seattle landscape, earning it the nickname 'Emerald City.' But what of its concrete core, where the average resident struggles to carve out a meaningful existence? What do the streets of Seattle have to teach us about who we are? Photographer Paulo Gonzales captures the everyday moments of living in Seattle, revealing the raw, unfiltered essence of urban life while exploring the very idea of identity.

“I guess I've always thought of the street as like—,” Gonzales searched for the right words. “It’s a public space, right? It’s like a dialogue and there’s this rhythm. There’s the way people represent themselves on the street which is definitely different than the way they would at home or in a more private setting. It's like you're walking down this street and you run into all kinds of people. And it's just always been interesting to me. It's almost like music in a way. You get all kinds of different music that have different rhythms and different tempos. And I think that's the way the street behaves or how maybe people behave on the street. People are walking differently. Talking at different tempos. Maybe people are running or you see someone on a bike. To me, it flows like music, in a way, and everyone's playing in this grand orchestra on the street.”

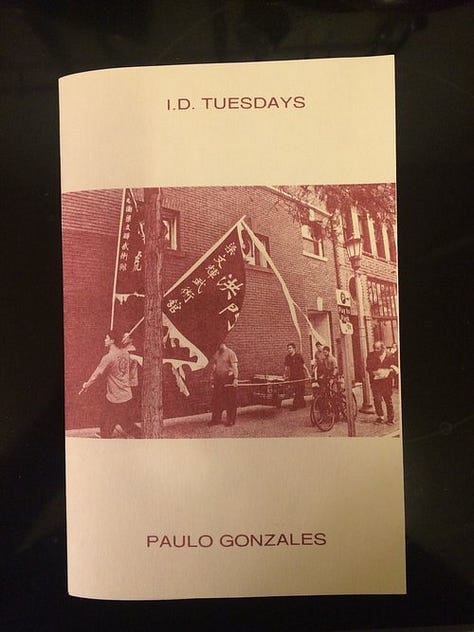

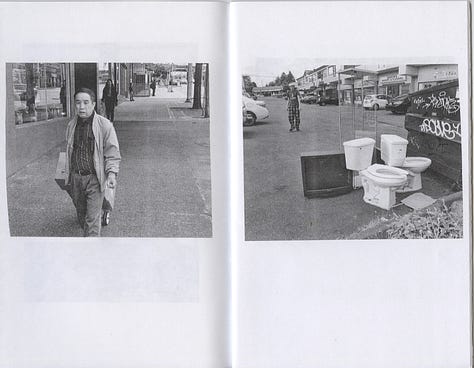

In Gonzales’ zine, ID Tuesdays, he explores Seattle’s International District (I.D.) neighborhood which is a diverse, mostly immigrant community just south of downtown. The gritty black and white photos feature a stern-faced youth with neck tattoos posed against a brick wall, an elder perched on a concrete bench while feeding a swarm of hungry pigeons, and a dumpster trinity of two porcelain toilets and a television hastily discarded in a strip-mall parking lot. But there are also other, softer moments captured in ID Tuesdays: An elder and a mother holding a baby carriage while gazing pensively at the camera. For Gonzales, these moments captured are as much about historical narrative and cultural perspective as they are about the current reality of a community.

“My family are immigrants,” said Gonzales, who was raised in California but has lived in Seattle for the past 11 years. “I guess I’m one and a half generations from Mexico. My mom's from Mexico and my dad’s from the Mexico border. And a lot of my family still lives in Mexico. … Definitely an immigrant background for me. So, when I went into that project, Id Tuesdays, I was thinking about the postmodern ideas as well: Who's going in to take a photograph of a neighborhood or a group of people? You know, traditionally, I think it's been sort of white male dominated when people have been documenting neighborhoods or people. And I thought, ‘Hey, wouldn't it be interesting if me— I have an immigrant background that's different from people in the International District, but what are those images going to look like? How do I view this neighborhood coming from a similar background?”

Gonzales said he was inspired by Bruce Davidson, a documentary and street photographer known for photographing immigrants and other underrepresented groups. One of Davidson’s most famous series was East 100th Street which documented a block in East Harlem, New York, during the 1960s. Davidson spent two years photographing the residents of this impoverished neighborhood, capturing their daily lives with a large-format camera. This series is celebrated for its intimate and respectful portrayal of the community, presenting the subjects with dignity and depth.

These historical photographs, even without descriptions, open a window into the past inhabitants of a place. In Gonzales’ zine Emerger: Found Photographs from Mexico City, the historical photographs he includes put the city and its people into historical context, even without the specific context of the images. Gonzales said he’s committed to exploring this historical context whenever he photographs a community, much like Davidson did. By delving into the past, Gonzales aims to uncover the layers of history that shape the present, adding depth and meaning to his work.

“I think about historical matters,” said Gonzales, who is heavily influenced by postmodernist ideas. “Maybe even subconsciously, but sometimes very consciously when I'm thinking about a new project. So, I think about where am I now in history? How has history impacted me as a person? And how can I express those things in photography? So yeah, I consciously sometimes think about those things and then other times I don’t. But then it’s evident in the images as well.”

Historically, when photography depicted marginalized groups, the photographer was centered as the authority. The photographic subjects were silent while the photographer spoke, through photos, on their behalf. This created a power imbalance that left marginalized groups vulnerable to being misrepresented through photography. But postmodernists believed that misrepresentation could be mitigated or avoided altogether if marginalized groups were empowered to photograph their own lives.

“So, at Seattle University, I remember watching a documentary about these children in India that were given cameras as part of a photography project,” Paulo Gonzales said. “And so, the whole idea of this project was that you're putting the power in people's hands to document their own lives. It's not an outsider coming in from the first-world to go in and photograph people and literally frame them in a photograph a certain way.”

In 2004, the documentary Born into Brothels: Calcutta’s Red Light Kids follows the journey of photographer Zana Briski and a group of children whose parents were prostitutes in Sonagachi, Kolkata’s red light district. The children were taught photography and given cameras so that they could depict life in their community through their own eyes. At least one of the children featured in Born into Brothels —Avijit Halder — went on to become an interdisciplinary artist and photographer in New York City.

“I would say the way that my education at Seattle University influenced or shaped my photography was, obviously, learning more about other photographers,” said Gonzales. And honestly, photographic history and art history too was such an interest. And to think about photography and art in general, through the scope of history, made a huge impact in my practice and in the way I look at photography now.”

Paulo Gonzales got his start in photography when he took a black-and-white photo class in high school, but he comes from a family of creatives.

“My dad and my brother were artists,” Gonzales said. “They liked to paint on canvas. So, I grew up with that kind of influence. And I always wanted to be good at drawing, but I never really had a knack for it. I was never really, I guess maybe disciplined enough to kind of sit there and sketch something out and draw something out and paint something out. But I knew I still needed to make something or I wanted to make something. And I think that while photography does take a lot of patience — especially analog black-and-white photography — it was more of an immediate sort of process for me. So as soon as I could take a photo and develop negatives, I was like, ‘Ah, well, I can compose something and express myself with this tool.’ So, for me it made sense, right? I liked the immediacy of it, I guess.”

Gonzales likes to display his photographs in zines — small, self-published booklets he distributes through Piggy Bank Zines, a Seattle-based zine collective.

“The last project is entitled Leprechaun,” said Gonzales. “So, there's this elaborate St. Patrick's Day display outside of a bar on Capitol Hill. Every St. Patrick’s Day I walk by it and it sort of disrupts my vision. ‘I'm like, whoa! What is this thing?’ And there's a display of an inflatable leprechaun. It's more of a humorous kind of project. So, I got in contact with the owner of the bar. And I said, ‘Hey, is it cool if I take photographs with people?’ And he said it was okay. And so, as people were coming in, I asked them if they wanted to pose next to this inflatable leprechaun. And it was just interesting the way people were wanting to represent themselves with this inanimate object, you know? You get all kinds of people posing, you know? And this whole idea of portraiture and how you want to be represented is kind of evident in that zine. … I don't know these people. I'm not talking to them. I don't know their background story. But you see different ways of engagement with this inanimate object. So, some people seem more confident, or some people seemed more humorous. Or maybe some people seemed a little more shy with the way they were posing next to it. So, you get a sense of how they felt next to this thing. At the end of the day, and I've talked to other photographers about this project, they observed that it was more about the inanimate inflatable leprechaun than the people.”

Approaching people on the street for a portrait is something Gonzales does often, but he also likes to capture images candidly, “shooting from the hip.” He uses simple point-and-shoot digital cameras like Olympus Pen and Lumix because they offer an immediacy and ease that helps in focusing on the content of the image over the technical aspects when doing street photography and featuring them in a zine.

“I think in photography, you can get really wrapped up into things like, what your tones are going to look like in the darkroom, what kind of lens you use, what kind of paper you use to print. There are so many variables, that in the end, to me, it's all about what the information is in the image. And so, letting go of all these things, like the type of paper I use, the lens I use, the equipment that I use, I can let go of all that if I'm making a zine. So, I can take a photograph with a decent camera and produce an image and photocopy it. You know, at that point, the photocopy machine takes control, not me. I can control it to a certain extent, but there's a lot of letting go there that feels liberating. It's not like I'm trying to get the specific way that it works. And I like that, I think it's freeing.”

© Copyright 2024 - Artists Up Close/Beverly Aarons. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

For permission requests, write to the author, addressed “Attention: Permissions Coordinator,” at the email address below.

[artistsupclose@gmail.com]

Our next event is Thriving Through Failure: Lessons From A Fashion Doll Reject, Friday, June 21, 2024 at 7pm. You can attend in-person or online. Get your tickets today!